Uran am Grand Canyon – Gefahr für Havasupai und andere ‚Native Americans‘, die Umwelt und eine World Heritage Site

Mai 2024

Quelle: https://ktar.com/story/5525870/watch-president-joe-biden-speaks-in-arizona-

about-creating-grand-canyon-monument-conservation/ 5 :32

In den vergangenen Jahren hatten wir kontinuierlich über die Entwicklungen in Sachen drohendem Uranbergbau, Widerstand der Havasupai und vieler anderer Indigener Nationen sowie von Umweltschutz- und auch der Tourismusbranche berichtet.

Ein Gesetz, das eine weiträumige Umgebung des Grand Canyon endgültig unter Schutz stellen sollte (Grand Canyon Centennial Protection Act), hatte zwar das Abgeordnetenhaus passiert, war aber im Senat hängen geblieben.

Am 8. August 2023 erklärte US-Präsident Biden in einer Zeremonie am Grand Canyon Airfield eine Gebiet von rd. 1 Million acres (rd. 4.047qkm) um den Grand Canyon zum National Monument. Maja Tilousi-Little, die Tochter von Carletta Tilousi, Havasupai, die mit dem Havasupai Tribe seit Jahrzehnten gegen das geplante Uranbergwerk am Grand Canyon aktiv ist, eröffnete die Veranstaltung und hieß Präsident Biden willkommen. Mit Biden’s Unterschrift wurde das „Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument“ rechtsgültig.

Welche Bedeutung hat das für die Zukunft?

So erfreulich diese Entwicklung ist, wird sie von der Gesetzeslage und von Uranbergbau-Unternehmen wie Energy Fuels konterkariert: die Erklärung des National Monument-Gebietes hebt ältere (Bergbau-)Rechte – also schon vor Einrichtung des National Monuments vorhandene Rechte – nicht auf.

So erfreulich diese Entwicklung ist, wird sie von der Gesetzeslage und von Uranbergbau-Unternehmen wie Energy Fuels konterkariert: die Erklärung des National Monument-Gebietes hebt ältere (Bergbau-)Rechte – also schon vor Einrichtung des National Monuments vorhandene Rechte – nicht auf.

Am 11. Januar 2024 schrieb der Havasupai Tribal Council: „Schweren Herzens müssen wir bestätigen, dass unsere schlimmsten Befürchtungen wahr geworden sind. Trotz Jahrzehnten aktiver und unermüdlicher Opposition , hat Energy Fuels, eine ausländische, gewinnorientierte Bergbaugesellschaft in ihrem eigennütziges Interesse gehandelt, toxisches Uran in der Pinyon Plain Mine (früher „Canyon Mine“) abgebaut, und damit einen unserer heiligsten Plätze entweiht und die Existenz der Havasupai aufs Spiel gesetzt.“

Energy Fuels war vor vielen Jahren in den Besitz des damals noch Canyon Mine genannten Uranbergwerks gekommen. Aufgrund des niedrigen Uranpreises war ein Abbau nicht wirtschaftlich interessant. Der Uranbergbau ist in den USA seit vielen Jahren rückläufig und war nahezu zum Erliegen gekommen (Uranproduktion 2023: ca. 101 t U), eine geringer Prozentsatz des für US-Atomkraftwerke benötigten Urans.

Auch die Uranverarbeitung in den sog. Uranmühlen – chemischen Fabriken, in denen das Gestein zuerst verkleinert, danach das Uran ausgelaugt wird – tendiert gegen Null. Die letzte Uran"mühle", White Mesa Mill, befindet sich in Blanding, Utah – und verarbeitet längst kein Uranerz mehr, sondern versucht, seltene Mineralien aus Abraum zu gewinnen.

Aufgrund des Krieges in der Ukraine und der Sanktionen, die gegen Russland beschlossen wurden bzw. werden, ist nun auch Uran betroffen. Bislang bezogen die USA 12% des benötigten Urans aus Russland, weitere 25% aus Kasachstan, das von manchen in USA als Russland nahestehend betrachtet wird. (Damit ist die Abhängigkeit der USA von russischem Uran gering als in der EU: hier werden ca. 25% des Urans aus Russland bezogen, Sanktionen gibt es seitens der EU bisher nicht).

Im Mai 2024 beschlossen die USA ein Gesetz, das Uranimporte aus Russland 90 Tage nach in Kraft treten des Gesetzes verbietet, wobei Ausnahmen möglich sein werden falls keine anderen Bezugsquellen verfügbar sind; erst 2028 soll dann der Bezug von Uran aus Russland endgültig beendet werden.

Nichtsdestoweniger ist die Richtung klar: Die USA wollen sich von russischen Uranlieferungen unabhängig machen. Uranfirmen wie Energy Fuels, UrEnergy und andere warten nur darauf, dass in USA wieder ein Markt für Uran entsteht – denn nur dann können sie ihr Geschäft gewinnbringend betreiben; mit den Lieferanten aus der ‚östlichen Hemisphäre‘, sei es Russland, sei es Kasachstan, können sie nicht konkurrieren.

Die Indigenen hatten diese Gefahr für ihr Land schon im Mai 2022, bald nach Beginn des Krieges in der Ukraine gesehen, wie die New York Times berichtete.

Der lange Weg des Uran ...

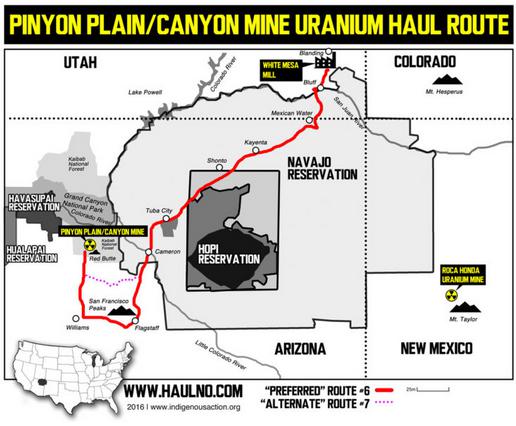

Der Lange Transportweg des Urans von der Pinyon Plains (Canyon) Mine durch die Navajo Reservation zur Uranverarbeitungsanlage in Blanding / Utah. Quelle: https://haulno.com/

Ein weiteres Problem stellt die Verarbeitung des Uranerzes dar: die nächste Uran’mühle‘ befindet sich in Blanding / Utah, rd. 400km entfernt. Bislang wird das abgebaute Uranerz offenbar auf dem Bergwerksgelände gelagert.

Uranerz, das in der Pinyon Plain (ex Canyon) Mine auf der Südseite des Grand Canyon gewonnen wird, kann nicht vor Ort verarbeitet werden: es gibt keine Verarbeitungsanlage, und sie wäre in der Region (National Park, nun auch National Monument) auch nicht genehmigungsfähig. Der Bau einer Uranverarbeitungsanlage würde beträchtliche

Kosten verursachen, die sich für relativ kleine Uranvorkommen der Pinyon Plain Mine kaum lohnen dürfte. Selbstverständlich will Energy Fuels das Uranerz lieber – kostengünstiger – in der vorhandenen Anlage, White Mesa Mill, verarbeiten. Damit muss das Uranerz über rd. 250 Meilen (rd. 400km) zur White Mesa Mill in Blanding / Utah transportiert werden. Ein guter Teil des Weges führt durch die Navajo Reservation. Am 15. Januar 2024 warnte der Präsident der Navajo Nation, Buu Nygren, dass solche Uranerztransporte, die die Navajo Reservation durchqueren müssten, gegen deren Gesetz verstoße. Quelle 1 / Quelle 2

Die Navajo Nation hatte nach den katastrophalen Auswirkungen des Uranbergbaus in den 1960er und 1970er Jahren, unter dessen Folgen die Reservation bis heute leidet, 2005 eine klare Position gegen Uranbergbau eingenommen; sie wurden dafür mit einer ‚Special Recognition‘ des Nuclear-Free Future Awards geehrt.

2008 wurde jedweder Abbau und Verarbeitung von Uran auf dem Gelände der Navajo (Dine) Reservation untersagt. Allerdings erstreckt sich die Gesetzgebungs-und Durchsetzungsgewalt des Navajo Council nicht auf die Interstate (rot markiert), auch wenn diese durch die Reservation führt.

... zur White Mesa Mill, Blanding / Utah

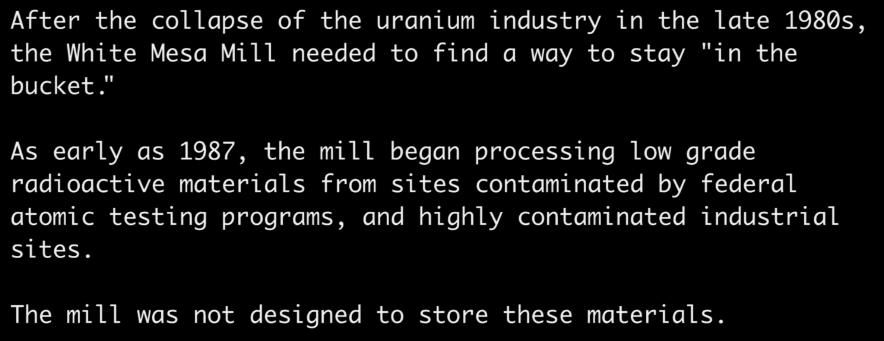

Das Uranerz aus der Pinyon Plain (ex Canyon) Mine soll nach dem 400km Transport in der Uran’mühle‘ von Blanding, Utah, verarbeitet werden. Die Verarbeitungsanlage, beschönigend Uran’mühle‘ (in Wirklichkeit eine chemische Fabrik mit Absetzbecken für die toxischen Rückstände) war während des Uranbooms vor mehr als 40 Jahren gebaut worden. Mit dem Ende des Uranbooms in den USA war sie an sich obsolet geworden. Zuletzt hatte sie sich im Besitz des Uranbergbau-Unternehmens Denison befunden.

(aus dem Kurzfilm: „Half Life – The Story of America’s Last Uranium Mill“, www.grandcanyontrust.org/half-life-story-americas-last-uranium-mill-0)

Im Juni 2012 erwarb Energy Fuels Inc. das Werk von Denison, vermutlich aus ‚strategischen Gründen‘, da es die Möglichkeit für die Weiterverarbeitung eventuell gewonnenen Uranerzes in der Region darstellt, die Energy Fuels Inc. dringend benötigt, sollte das Unternehmen jemals dazu kommen, am Grand Canyon Uran abzubauen (was dem Unternehmen seit Gründung 2006 am Canyon nicht gelungen war).

Um das Werk am Laufen zu halten, und zumindest die Kosten zu decken, war schon in den späten 1980er Jahren begonnen worden, geringer kontaminiertes radioaktives Material aus staatlichen Atomtestprogrammen und von stark kontaminierten industriellen Stätten zu verarbeiten.

Man sah sich weiterhin nach „alternative feeds“ um, nach Material, mit dem die Anlage gefüttert werden kann, um im Geschäft zu bleiben, und aus dem eventuell wertvolle Stoffe gewonnen werden könne; die Abfälle, vieles in flüssiger Form, wird auf dem Firmengelände (end)gelagert – was das Gelände zu einem Endlager für radioaktive und toxischen Stoffe macht, wofür das Unternehmen keine Genehmigung hat.

Energy Fuels geriet infolgedessen immer wieder mit den Umweltschutzbehörden in Konflikt. Eine Seite auf WISE Uranium Project listet die Verstöße detailliert auf.

Die in der Region lebenden Ute begannen sich um ihre Wasserversorgung zu sorgen, da alle möglichen Abfälle in Becken abgelagert wurden, von denen einige vor 30 oder 40 Jahren angelegt worden waren, und deren Plastikfolien allmählich undicht werden. Ab 2017 organisierten die Ute jährlich Protestmärsche gegen den Betrieb der White Mesa Mill.

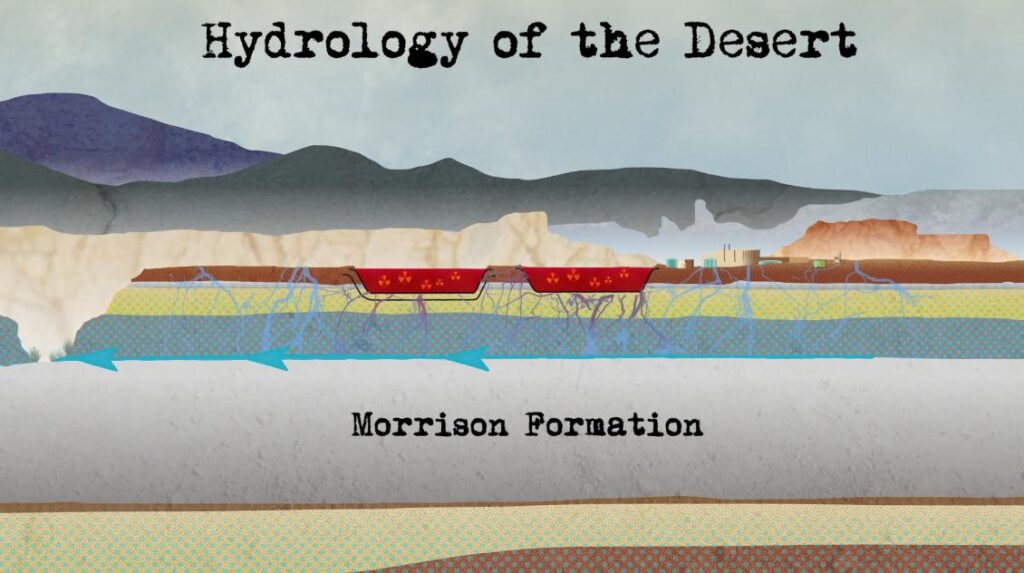

Eine NGO namens HEAL Utah nahm die White Mesa Mill und die Umgebung unter die Lupe. Es stellte sich heraus, dass die Abwasserbecken, in denen schwer verschmutztes Wasser abgelagert wird, teilweise lecken, Damit können gesundheitsgefährdende Stoffe in den Grundwasserleiter, das Navajo Aquifer gelangen – und damit die Wasserversorgung in der Region gefährden.

Die Absetzbecken der White Mesa Mill liegen direkt über zwei Grundwasserleitern; aus dem näher zur Oberfläche liegenden wird die Wasserversorgung u.a. für den Ute Mountain Tribe gespeist.

Im November 2023 berichtete auch der SPIEGEL über wieder aufstrebenden Uranbergbau in den USA und über die White Mesa Mill in Blanding unter dem Titel „Uran boomt – aber der wahre Preis dafür ist hoch“.

Das Bild zeigt schematisch die Absetzbecken der White Mesa Mill mit radioaktiven und giftigen Abwässern, die das Grundwasser gefährden, das später – den blauen Pfeilen folgend – an Quellen austritt – die dann kontaminiert sind. (Grafik aus dem Film: „Half Life – The Story of America’s Last Uranium Mill“, www.grandcanyontrust.org/half-life-story-americas-last-uranium-mill-0, 3:43)

Sollte die Kontamination das tieferliegende Navajo Aquifer, ein ausgedehntes Grundwasservorkommen erreichen, aus dem Städte im südöstliche Utah und nördlichen Arizona Trinkwasser entnehmen, wäre dies katastrophal.

Außerdem besteht die Gefahr, dass die White Mesa Mill eine „low cost radioactive waste disposal site“, ein billiges (End-)Lager für radioaktiven – bzw. giftigen – Müll wird. Betriebe aus den gesamten USA und aus Kanada sind interessiert, radioaktiven Müll über den Umweg der Uran’mühle‘ verarbeiten zu lassen, und die restlichen Abfallstoffe, radioaktiv und giftig, dort „endzulagern“. Dieses Geschäft treibt die White Mesa Mill, im Besitz von Energy Fuels, voran.

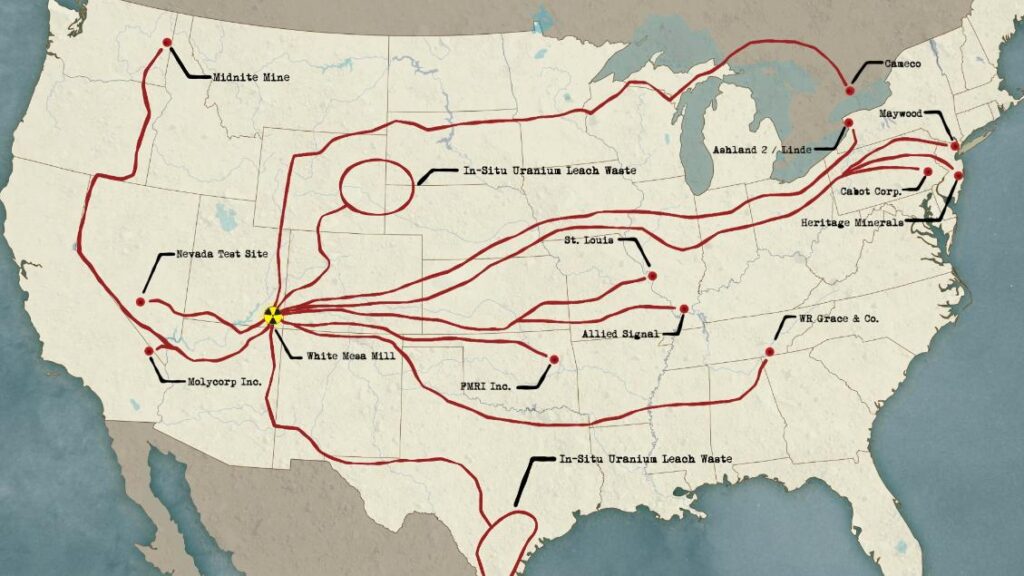

Die Grafik zeigt, dass aus verschiedensten Regionen der USA und sogar aus Kanada radioaktiver bzw. toxischer Müll zur White Mea Mill transportiert wird, um ihn dort verarbeiten und die Reste ‚endzulagern‘ zu lassen.

(Grafik aus dem Film: „Half Life – The Story of America’s Last Uranium Mill“,

www.grandcanyontrust.org/half-life-story-americas-last-uranium-mill-0, 6:06)

In dieser zweifelhaften Anlage will Energy Fuels dann das Uran aus der Pinyon / Canyon Mine verarbeiten. Der Abfall aus der Uranverarbeitung würde dann die Wasserversorgung einer anderen Indigenen Gruppe, des Ute Tribe, White Mesa Chapter, gefährden.

Sollten die radioaktiven und toxischen Elemente jemals in das Navajo Aquifer, den tiefer gelegenen, großen Grundwasserleiter unterhalb der ‚Morrison Formation‘ (siehe Bild), gelangen, wäre die Wasserversorgung von Blanding, Kayenta, Tuba City und vielen anderen Orten gefährdet.

Fazit

Der Abbau von Uran am Grand Canyon in der Pinyon Plains Mine stellt eine Gefahr für das Wasser dar, und damit auch für die im naheliegenden Canyon lebenden Havasupai.

Der Transport des Uranerzes über rd. 400km führt durch die Navajo Hopi Reservation, nach deren Gesetzen ein solcher Transport über ihr Land nicht zulässig ist.

Sollte das Uranerz dennoch nach Blanding zu Energy Fuels‘ Uranverarbeitungsanlage White Mesa Mill gelangen, besteht beträchtliche Gefahr, dass weitere Grundwasserleiter verschmutzt werden; die ersten Betroffenen sind wiederum Indigene, Angehörige des Ute Tribe.

Das Uranvorkommen am Grand Canyon, das Energy Fuels abbauen will, macht ungefähr 1 – 2% der gesamten Uranvorkommen in den USA aus; dies wirft auch die Frage auf, ob diese minimale Menge es wert ist, das Risiko einzugehen, dass große Grundwasservorkommen geschädigt werden.

Weiterführende Informationen

- Grand Canyon Trust website zu Uran/-bergbau

- „Half Life – The Story of America’s Last Uranium Mill“, 12 min, englisch

- Website und facebook site von “Haul No”

„Haul no“ setzt sich u.a. gegen den Transport von Uranerz durch die Navajo Reservation ein. - Der SPIEGEL-Artikel „Uran boomt – aber der wahre Preis dafür ist hoch“ (29. Nov. 2023) ist einer der wenigen deutschsprachigen ausführlicheren und kritischen Artikel zu der Thematik (Bezahlschranke).

Dieser Artikel erschien im Frühjahr 2024 in kürzerer Form im COYOTE, Zeitschrift der Aktionsgruppe Indianer und Menschenrechte (AGIM), München, und wurde im Mai 2024 aktualisiert.

Grand Canyon National Park

Under Attack by Uranium Mining Plans

from Günter Wippel, uranium network

published in World Heritage Watch Report 2018

Grand Canyon National Park has been inscribed as a World Heritage site in 1979, under criterions viii, ix and x of the UNESCO: „The Grand Canyon is among the earth’s greatest on-going geological spectacles. Its vastness is stunning, and the evidence it reveals about the earth’s history is invaluable. The 1.5-kilometer (0.9 mile) deep gorge ranges in width from 500 m to 30 km (0.3 mile to 18.6 miles). It twists and turns 445 km (276.5 miles) and was formed during 6 million years of geologic activity and erosion by the Colorado River on the upraised earth’s crust. (...) Horizontal strata exposed in the canyon retrace geological history over 2 billion years and represent the four major geologic eras.“ „There are also prehistoric traces of human adaptation to a particularly harsh environment.“ [1]

Grand Canyon National Park has been inscribed as a World Heritage site in 1979, under criterions viii, ix and x of the UNESCO: „The Grand Canyon is among the earth’s greatest on-going geological spectacles. Its vastness is stunning, and the evidence it reveals about the earth’s history is invaluable. The 1.5-kilometer (0.9 mile) deep gorge ranges in width from 500 m to 30 km (0.3 mile to 18.6 miles). It twists and turns 445 km (276.5 miles) and was formed during 6 million years of geologic activity and erosion by the Colorado River on the upraised earth’s crust. (...) Horizontal strata exposed in the canyon retrace geological history over 2 billion years and represent the four major geologic eras.“ „There are also prehistoric traces of human adaptation to a particularly harsh environment.“ [1]

„Over 2,000 prehistoric Indian ruins have been recorded in the park. (...) The ruins contain evidence that the earliest human inhabitants of the canyon were gatherers and hunters. (...) ... discovery of split-twig figurines ... Radioacarbon dating has shown some of the figurines to be 4,000 years old.“ [2]

Since the 1950s, uranium mining had been a major operation in the Southwest US, leaving a legacy of unreclaimed uranium mines, mills, tailings and tailings ponds, some of them currently under reclamation.

In the mid-1980ies, a uranium mine was developed close to Red Butte: the Canyon Mine, approx. six miles outside the World Heritage Site, south of Grand Canyon village. The mine site is outside the World Heritage site, located in Kaibab National Forest which is under administration of the US Forest Service. [3]

Although the mine site is not on the World Heritage site territory, there is major risk that radioactive contamination may reach the WHS

either through flash foods typical for the region, via the Havasu Canyon leading to the Grand Canyon (many flash floods occurred, e.g. in 1993, 2008, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2017)

or via a groundwater aquifer (Redwall Muav aquifer) which extends from the mine area towards Havasu Canyon; the area is ‘karst’, and groundwater movement is not very well understood.

According to a USGS study of 2016 [4], groundwater discharges into Havasu Creek; this groundwater may get contaminated by uranium mining of a geological formation called “breccia pipes”, as in the Canyon Mine - and then reach Havasu Creek and finally the Grand Canyon. The Havasupai Tribe, a recognized Indian tribe inhabiting the Havasu Canyon, had opposed the development of the mine for this reason.

The Canyon Mine project came to a halt in 1991 due to a decline of the price of uranium. To this point in time, no uranium ore had been mined. The company, Energy Fuels Nuclear went bankrupt later on. Ownership of the mine changed repeatedly until Canyon Mine ended up with Energy Fuels Inc., founded in 2006 (with no connections except for the similarity of name, to former Energy Fuels Nuclear). A sudden rise of the spot market price of uranium in 2007/2008 had sparked new interest in uranium mining.

In 2012, under Obama administration, Secretary of State Ken Salazar withdrew an area around Grand Canyon for 20 years from all new uranium developments (“withdrawal” or, colloquially called ‘ban’) which was welcomed by the UNESCO WHC [WHC Decision 40 COM 7B.104]. The uranium ban, however, does not apply to pre-existing mines and claims such as Canyon Mine as well as several mines on standby and to claims; these mines might commence production at short notice once the price of uranium rises. In 2016, activities at Canyon Mine were restarted, until in Mach 2017, an ‘unexpected influx of water’ brought sinking of the shaft to another halt.

The UNESCO WHC opinion and 2016 Decision UNESCO WHC expressed in 2016 serious concerns, stating, among other issues: „It should be noted in particular that the EIA for the Canyon Mine project, which was temporarily closed in 2013, dates back to 1986. It is therefore crucial that a new EIA, including an assessment of the potential impact on the OUV, is conducted before operation of this project is permitted to resume. [WHC/16/40.COM/7B.Add, underline not in the original text]

The concerns are reflected in the 2016 WHC Decision [40 COM 7B.104]

Requests the State Party to ensure that Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) are completed for the proposed uranium mining developments, particularly prior to resuming operations for the Canyon Mine project, temporarily closed in 2013, which should include a specific assessment of the impact on the OUV, in line with IUCN’s World Heritage Advice Note on Environmental Assessment;

The UNESCO WHC opinion and 2016 Decision

UNESCO WHC expressed in 2016 serious concerns, stating, among other issues: „It should be noted in particular that the EIA for the Canyon Mine project, which was temporarily closed in 2013, dates back to 1986. It is therefore crucial that a new EIA, including an assessment of the potential impact on the OUV, is conducted before operation of this project is permitted to resume. [WHC/16/40.COM/7B.Add, underline not in the original text]

The concerns are reflected in the 2016 WHC Decision [40 COM 7B.104]

Requests the State Party to ensure that Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) are completed for the proposed uranium mining developments, particularly prior to resuming operations for the Canyon Mine project, temporarily closed in 2013, which should include a specific assessment of the impact on the OUV, in line with IUCN’s World Heritage Advice Note on Environmental Assessment;

No action of the State Party are known implementing this request. The WHC’s Decision and recommendations were not taken into account.

In December 2017, the Court of Appeals decided that the 1986 EIA – by then, 31 year old – was good enough to proceed with uranium mining in 2018, rejecting a complaint by the Havasupai Tribe, the Grand Canyon Trust, the Center for Biological Diversity and the Sierra Club, basically on technical-legal reasons. [5]

It has to be noted that the 1986 EIA for the Canyon Mine contains no evaluation of (potential) impacts of the mine on the World Heritage Site Grand Canyon, no consideration of the World Heritage status of nearby Grand Canyon is made in the 1986 EIA at all, althought the site had been inscribed to the World Heritage already in 1979.

In addition, more uranium mines in the area pose a danger to World Herirage Site Grand Canyon; in items no. 4 and 5 of the 2016 decision, the WHC ... „Notes with significant concern that there are 11 consented uranium mining proposals in the area surrounding the property that are exempt from the 20-year withdrawal” and “Reiterates its position that mineral exploration or exploitation is incompatible with World Heritage status ...”. No action by the State Party is known concerning other mining projects and uranium claims in the area of the World Heritage site or affecting it.

The Ban, the Companies, US National Security and Latest Developments

The Court of Appeals – although giving Canyon Mine a green light – upheld in its December 2017 decision the ban for new uranium mining projects in the “withdrawal zone”. However, in mid-January 2018, Energy Fuels and Ur-Energy filed a petition, claiming “Our country cannot afford to depend on foreign sources – particularly Russia, and those in its sphere of influence, and China – for the element that provides the backbone of our nuclear deterrent, powers the ships and submarines of America’s nuclear Navy, and supplies 20% of the nation’s electricity.” [6]

The companies allege that US dependency on uranium imports from abroad would jeopardize National Security. They would like to have “25 percent of the U.S. market [reserved] for domestic uranium” – which then would be mined by US companies. This rather unprecedented move – if accepted by the administration – would grant US uranium companies a 25% market share; companies would then not need to compete with foreign companies – which might artificially spark a new uranium boom in the US – and put the Grand Canyon World Heritage site at additional risk.

Moreover, companies push hard to overthrow the uranium ban: In mid-March 2018, “two groups – the American Exploration and Mining Association (AEMA) and the National Mining Association – have submitted a new request to the Supreme Court, asking them to review the mining ban, enacted in 2012, that bans all uranium mining claims on the lands surrounding the national monument.” [7]

The (uranium) mining industry is aggressively pushing forward to mine uranium in close vicinity of the Grand Canyon, potentially affecting the World Heritage Site. The State Party is neither taking WHC concerns serious nor implementing any of the WHC 2016 Decision’s recommendations.

Uranium exploitation bears the risk to deprive the Havasupai Tribe of one their basic means of existence - water. This would amount to an infringement of their rights under the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and / or to a violation of the UN Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

At a hearing of the House Committee on Natural Resources, Havasupai Tribal Council member Carletta Tilousi testified on Dec. 12. 2017:

“The Havasupai People are very concerned about our main fresh water source, Havasu Creek, which flows right through the middle of our village. Havasu Creek is created by the Red Wall Mauve Aquifer, which supplies water for us and downstream cities towns like Kingman, Phoenix, Tucson, and Las Vegas. The largest uranium ore deposits in the United States are all located above the Red Wall Mauve Aquifer; therefore, the cancellation of the Withdrawal will open up the uranium ore located on Kaibab Forest Service Lands to uranium companies.

The spring water flows directly from the Red Wall Mauve Aquifer that lies directly beneath the plateau and peaks south of Grand Canyon. Opening up this area to uranium and other mining would be tragic and an environmental nightmare. What happens to that Red Wall Muave Aquifer and springs happens to the Havasupai People. I am here to tell you that uranium contamination in the aquifer will not only poison my family, my Tribe, ancestral lands, and me, but also millions of people living downstream.

The Tribe has great reason to be concerned. Thousands of uranium mining claims, like so many vials of poison, threaten those lands that are the source of our water. Scientists do not yet fully understand how mining uranium will affect the groundwaters and watershed.” [9]

References

[1] http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/75

[2] http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/75/multiple=1&unique_number=81 à MAPS

[3] https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/kaibab/home/?cid=fsm91_050263

[4] U.S. Geological Survey, Scientific Investigations Report 2005–5222, Version 1.1, March 2016 https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2005/5222/sir2005-5222_text.pdf

[5]UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT, No.15-15754, D.C.No.3:13-cv-08045-DGC

[6] www.politico.com/newsletters/morning-trade/2018/01/17/another-section-232-investigation-on-the-horizon-075366

[7] www.nationofchange.org/2018/03/13/uranium-industry-begs-supreme-court-to-mine-next-to-the-grand-canyon/

[8] https://theconversation.com/before-the-us-approves-new-uranium-mining-consider-its-toxic-legacy-91204

[9] Comment by Carletta Tilousi, Havasupai Tribal Council Member at the HOUSE COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES, 115th Congress Disclosure Form, Examining Consequences of America’s Growing Dependence on Foreign Minerals, December 12, 2017 http://docs.house.gov/meetings/II/II06/20171212/106736/HHRG-115-II06-Wstate-TilousiC-20171212.pdf

READ MORE

Uranabbau am Grand Canyon

Entscheidungsphase über Moratorium

von Monika Seiller

Am 10. März 2011 hat die Umweltbehörde Arizona Department of Environmental Quality(ADEQ) den Anträgen der Denison Mines Corp. zum Betrieb von drei neuen Uranminen am Grand Canyon im US-Bundesstaat Arizona stattgegeben und eine Genehmigung im Hinblick auf Wasser- und Luftqualität erteilt. Der Betreiber hat damit einen Teilerfolg hinsichtlich der geplanten Uranminen in Arizona erzielt. Im Augenblick besteht noch ein Moratorium des Innenministeriums, das weitere Uranprojekte in der Region um das Naturwunder aussetzt. Von dem Abbau unmittelbar betroffen wären u.a. die Havasupai, die sich seit langem gegen den Uranabbau wehren.

erschienen in COYOTE Nr. 89 / Frühjahr 2011

NEWS

Uranium mining, native resistance, and the greener path (Orion magazine)

The impact of uranium mining on indigenous communities by Winona LaDuke Published in the January/February 2009 issue of Orion magazine IN A DINE CREATION STORY, the people were given a choice of two yellow powders. They chose the yellow dust of corn pollen, and were instructed to leave the other yellow powder—uranium—in the soil and…

Read More